South Africa’s National Treasury announced on 24 April 2025 that the planned VAT hike to 15.5% — set to take effect on 1 May — would be withdrawn. The declaration made headlines and temporarily calmed political and public anxiety. But the announcement has not been accompanied by a clear legal roadmap, and with Parliament on recess, a public holiday looming, and no amended legislation in sight, the question is pressing: What can government legally do now — and quickly — to make this reversal real?

In this article, we explore the fastest viable legal options to withdraw the VAT increase lawfully, explain why certain routes are closed, and identify what must happen by when to avoid a constitutional and administrative crisis.

Why the Reversal Cannot Be Just a Statement

The VAT rate in South Africa is set by legislation, not executive announcement. The Rates and Monetary Amounts and Amendment of Revenue Laws Act, tabled annually, legally enforces tax rate changes, including VAT. If that Act — as passed or pending — includes a VAT hike from 15% to 15.5%, it must be formally amended or repealed by Parliament. Treasury cannot undo it with a press release or internal directive. Section 2 of the Constitution requires that all conduct, including executive conduct, complies with the law. A mere administrative withdrawal, without legislative repeal, is therefore unconstitutional.

Time Constraints: Parliament Is in Recess

Here’s where the real bottleneck lies. After the 24 April announcement:

- 28 April is a public holiday (Freedom Day observed),

- 29–30 April are recess days for Parliament,

- 1 May is Workers’ Day, another public holiday,

- And the VAT hike is scheduled to come into force on 1 May.

That gives the executive no sitting days to pass or withdraw the applicable legislation — unless an extraordinary procedural intervention occurs.

So, what are the options?

Option 1: Call a Special Sitting of Parliament (Most Legally Robust)

Under Joint Rule 3 of Parliament’s Rules and Orders, the Speaker of the National Assembly and the Chairperson of the NCOP can summon a special sitting during recess, provided it is “in the public interest.” The executive could request this sitting specifically to:

- Table an urgent amendment to the Rates Bill (or the VAT-related clauses in the 2025 Revenue Laws Act),

- Debate and vote on the change,

- Ensure the amended bill is passed and assented to by the President,

- And published in the Government Gazette by 30 April.

This is procedurally heavy, but constitutionally clean and immune from judicial challenge. However, the clock is working against this option unless the sitting is convened immediately and cross-party consensus is secured to expedite the process.

Option 2: Withdraw the VAT Clause via Ministerial Notice and Post-Date Repeal (Technically Risky)

If the enabling legislation (Rates Act 2025) delegates power to the Minister of Finance to determine the effective date of tax changes by notice in the Gazette, then the Minister could issue a non-implementation notice for the VAT hike before 1 May. This buys time to process a full legislative repeal after the recess.

However, this option is only valid if such delegation exists in the Act. If not, it’s ultra vires — beyond legal power. Relying on this mechanism without statutory support may open the door to litigation by taxpayers or Parliament itself.

Option 3: Presidential Proclamation of Suspension (Extremely Limited and Constitutionally Frail)

In terms of section 81 of the Constitution, the President may sign a bill but delay its commencement by proclamation in the Gazette. This tool is only available if:

- The bill has not yet commenced, and

- The VAT hike is contained in a law not yet proclaimed into force.

If the VAT hike was already enacted with a fixed future date (1 May 2025), this mechanism cannot stop it — the law will self-execute unless amended.

Presidential proclamations are not repeal mechanisms. They can delay implementation, but not undo it. This is a last resort if legal drafters designed the VAT clause to be flexible in commencement — a rare, but not impossible, scenario.

Option 4: Pass a Retroactive Amendment After Recess (Legally Sound, Politically Risky)

If the hike takes effect on 1 May but Parliament only reconvenes in early May, government could pass a retroactive amendment repealing the hike with effect from 1 May. Section 4 of the Interpretation Act 33 of 1957 allows Parliament to make laws with retrospective effect, including revenue laws, provided this is expressly stated.

This route creates legal clarity but operational mess:

- Retailers would have to reverse VAT invoices,

- SARS would need to refund over-collections,

- And it could trigger public litigation from affected businesses.

It is legally permissible but administratively disruptive and politically costly.

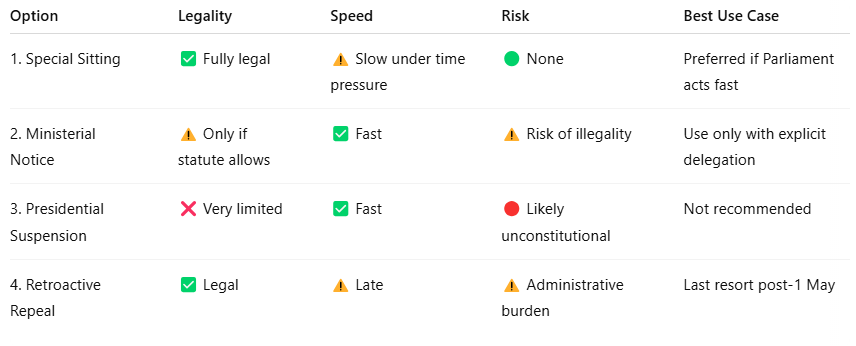

Summary of Options – From Fastest to Cleanest

What Government Should Do Today

- Immediately request a special sitting of Parliament under Joint Rule 3.

- If not viable, review the enabling clause of the Rates Bill to assess whether the Minister has lawful power to halt implementation via Gazette notice.

- Inform SARS and the public of the interim legal position to prevent unlawful under- or over-collection of VAT.

- Prepare a repeal bill with retrospective effect, in case nothing can be done before 1 May.

Final Word: There Is No Shortcut to the Rule of Law

The Constitution demands that all revenue and expenditure be authorised by law. The executive cannot govern tax policy by announcement. Parliamentary oversight, statutory compliance, and procedural rigour are non-negotiable in a constitutional democracy.

Unless government acts within the bounds of lawful options — and quickly — South Africa may find itself in a legal twilight zone where a tax rate is both declared dead and legally alive. That is not governance. That is constitutional risk.